Abstract

Background and purpose

Loss to follow-up in observational studies may skew results and hamper study reliability. We evaluated the importance of loss to follow-up in the Swedish spine register.

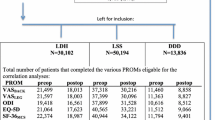

Patients

Patients operated in the lumbar spine and scheduled for a postal questionnaire follow-up during part of 2016 were identified. Out of the 351 patients, 203 had responded. After multiple attempts, 115 of the 148 non-responders were reached; 68 returned the complete questionnaire; and 47 answered a brief questionnaire by phone. Analyses were made with the Chi-square test, analysis of covariance or logistic regression. Some analyses were adjusted.

Results

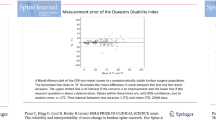

At baseline, the non-responders were younger than the responders (55 vs 61 years, p < 0.001) and had higher Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) (54 vs 48, p = 0.003), lower SF-36 physical component summary score (PCS) (36 vs 40, p = 0.011) and lower EQ-5D (0.17 vs 0.27, p = 0.018). Mean back pain, leg pain, ODI, EQ-5D, SF-36 mental component summary score (MCS) improved significantly in both groups (all p < 0.001). SF-36 PCS did not improve in the non-responder group (p = 0.063). Non-responders perceived less improvement in back pain (global assessment back 60% vs 72%, p = 0.002). At follow-up, there were no differences in patient-reported outcome measures between the groups (all p ≥ 0.06), with the exception of a lower SF-36 MCS among the non-responders (p = 0.015).

Interpretation

After surgery for lumbar spine degenerative disorders, non-responders achieve similar outcome as responders in the Swedish spine register, with the exception of a lower mental health and less perceived improvement in back pain.

Graphic abstract

These slides can be retrieved under Electronic Supplementary Material.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Strömqvist B et al (2013) Swespine: the Swedish spine register: the 2012 report. Eur Spine J 22(4):953–974

Gliklich RE, Dreyer NA, Leavy MB (2014) Registries for evaluating patient outcomes: a user’s guide [internet]. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville

Hoy D et al (2014) The global burden of low back pain: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis 73(6):968–974

Solberg TK et al (2011) Would loss to follow-up bias the outcome evaluation of patients operated for degenerative disorders of the lumbar spine? Acta Orthop 82(1):56–63

van Amelsvoort LG et al (2004) The effect of non-random loss to follow-up on group mean estimates in a longitudinal study. Eur J Epidemiol 19(1):15–23

Powers J et al (2015) Loss to follow-up was used to estimate bias in a longitudinal study: a new approach. J Clin Epidemiol 68(8):870–876

Elkan P et al (2018) Response rate does not affect patient-reported outcome after lumbar discectomy. Eur Spine J 27(7):1538–1546

Kristman V, Manno M, Cote P (2004) Loss to follow-up in cohort studies: how much is too much? Eur J Epidemiol 19(8):751–760

Højmark K et al (2016) Patient-reported outcome measures unbiased by loss of follow-up. Single-center study based on DaneSpine, the Danish spine surgery registry. Eur Spine J 25(1):282–286

Asch DA, Jedrziewski MK, Christakis NA (1997) Response rates to mail surveys published in medical journals. J Clin Epidemiol 50(10):1129–1136

Peter Fritzell OH, Paul G, Allan A, Anna S, Catharina P, Olof T, Björn S (2017) Swedish lumbar spine study, group. In: Swespine annual register report 2017

Endler P et al (2017) Outcomes of posterolateral fusion with and without instrumentation and of interbody fusion for isthmic spondylolisthesis: a prospective study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 99(9):743–752

Hagg O et al (2002) Simplifying outcome measurement: evaluation of instruments for measuring outcome after fusion surgery for chronic low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 27(11):1213–1222

Fairbank JC, Pynsent PB (2000) The Oswestry disability index. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 25(22):2940–2952

Hjermstad MJ et al (2011) Studies comparing numerical rating scales, verbal rating scales, and visual analogue scales for assessment of pain intensity in adults: a systematic literature review. J Pain Symptom Manag 41(6):1073–1093

Burstrom K, Johannesson M, Diderichsen F (2001) Swedish population health-related quality of life results using the EQ-5D. Qual Life Res 10(7):621–635

Ware JE Jr (2000) SF-36 health survey update. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 25(24):3130–3139

Copay AG et al (2008) Minimum clinically important difference in lumbar spine surgery patients: a choice of methods using the Oswestry disability index, medical outcomes study questionnaire short form 36, and pain scales. Spine J 8(6):968–974

Wihlborg A, Akesson K, Gerdhem P (2014) External validity of a population-based study on osteoporosis and fracture. Acta Orthop 85(4):433–437

Suominen S et al (2012) Non-response in a nationwide follow-up postal survey in Finland: a register-based mortality analysis of respondents and non-respondents of the health and social support (HeSSup) study. BMJ Open 2(2):e000657

Juto H et al (2017) Evaluating non-responders of a survey in the Swedish fracture register: no indication of different functional result. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 18(1):278

Pérez-Prieto D et al (2014) Should age be a contraindication for degenerative lumbar surgery? Eur Spine J 23(5):1007–1012

Thomas ML et al (2016) Paradoxical trend for improvement in mental health with aging: a community-based study of 1,546 adults aged 21–100 years. J Clin Psychiatry 77(8):e1019–e1025

Kovacs FM et al (2007) Minimal clinically important change for pain intensity and disability in patients with nonspecific low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 32(25):2915–2920

Solberg T et al (2013) Can we define success criteria for lumbar disc surgery?: estimates for a substantial amount of improvement in core outcome measures. Acta Orthop 84(2):196–201

Tafazal SI, Sell PJ (2006) Outcome scores in spinal surgery quantified: excellent, good, fair and poor in terms of patient-completed tools. Eur Spine J 15(11):1653–1660

Maillard J et al (2015) Preoperative and early postoperative quality of life after major surgery—a prospective observational study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 13:12

Sackett DL et al (2000) Evidence-based medicine—How to Practice and teach EBM, 2nd edn. Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh

Schulz KF, Grimes DA (2002) Sample size slippages in randomised trials: exclusions and the lost and wayward. Lancet 359(9308):781–785

Parai C et al (2018) The value of patient global assessment in lumbar spine surgery: an evaluation based on more than 90,000 patients. Eur Spine J 27(3):554–563

Rolstad S, Adler J, Ryden A (2011) Response burden and questionnaire length: is shorter better? A review and meta-analysis. Value Health 14(8):1101–1108

Tamcan O et al (2010) The course of chronic and recurrent low back pain in the general population. Pain 150(3):451–457

Elkan P et al (2016) Markers of inflammation and fibrinolysis in relation to outcome after surgery for lumbar disc herniation. A prospective study on 177 patients. Eur Spine J 25(1):186–191

Moller H, Hedlund R (2000) Surgery versus conservative management in adult isthmic spondylolisthesis–a prospective randomized study: part 1. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 25(13):1711–1715

Funding

This study was financially supported by funds from the Swedish Society of Spinal Surgeons. The funding body had no role in the analysis, the interpretation of data or the writing of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Endler, P., Ekman, P., Hellström, F. et al. Minor effect of loss to follow-up on outcome interpretation in the Swedish spine register. Eur Spine J 29, 213–220 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-019-06181-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-019-06181-0