Abstract

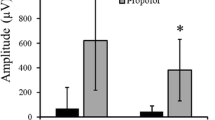

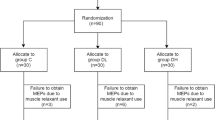

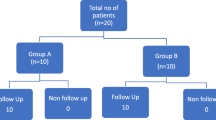

Total intravenous anesthesia (TIVA) with propofol and opioids is frequently utilized for spinal surgery when somatosensory evoked potentials (SSEPs) and transcranial motor evoked potentials (tcMEPs) are monitored. Many anesthesiologists would prefer to utilize low dose halogenated anesthetics (e.g. 1/2 MAC). We examined our recent experience using 3 % desflurane or TIVA during spine surgery to determine the impact on propofol usage and on the evoked potential responses. After institutional review board approval we conducted a retrospective review of a 6 month period for adult spine patients who were monitored with SSEPs and tcMEPs. Cases were included for the study if anesthesia was conducted with propofol–opioid TIVA or 3 % desflurane supplemented with propofol or opioid infusions as needed. We evaluated the propofol infusion rate, cortical amplitudes of the SSEPs (median nerve, posterior tibial nerve), amplitudes and stimulation voltage for eliciting the tcMEPs (adductor pollicis brevis, tibialis anterior) and the amplitude variability of the SSEP and tcMEP responses as assessed by the average percentage trial to trial change. Of the 156 spine cases included in the study, 95 had TIVA with propofol–opioid (TIVA) and 61 had 3 % expired desflurane (INHAL). Three INHAL cases were excluded because the desflurane was eliminated because of inadequate responses and 26 cases (16 TIVA and 10 INHAL) were excluded due to significant changes during monitoring. Propofol infusion rates in the INHAL group were reduced from the TIVA group (average 115–45 μg/kg/min) (p < 0.00001) with 21 cases where propofol was not used. No statistically significant differences in cortical SSEP or tcMEP amplitudes, tcMEP stimulation voltages nor in the average trial to trial amplitude variability were seen. The data from these cases indicates that 1/2 MAC (3 %) desflurane can be used in conjunction with SSEP and tcMEP monitoring for some adult patients undergoing spine surgery. Further studies are needed to confirm the relative benefits versus negative effects of the use of desflurane and other halogenated agents for anesthesia during procedures on neurophysiological monitoring involving tcMEPs. Further studies are also needed to characterize which patients may or may not be candidates for supplementation such as those with neural dysfunction or who are opioid tolerant from chronic use.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Alkire MT, Hudetz AG, Tononi G. Consciousness and anesthesia. Science. 2008;322(5903):876–80.

Woodforth IJ, Hicks RG, Crawford MR, Stephen JP, Burke DJ. Variability of motor-evoked potentials recorded during nitrous oxide anesthesia from the tibialis anterior muscle after transcranial electrical stimulation. Anesth Analg. 1996;82(4):744–9.

Lyon R, Feiner J, Lieberman JA. Progressive suppression of motor evoked potentials during general anesthesia: the phenomenon of “anesthetic fade.” J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2005;17(1):13–9.

Darling WG, Wolf SL, Butler AJ. Variability of motor potentials evoked by transcranial magnetic stimulation depends on muscle activation. Exp Brain Res. 2006;174(2):376–85.

Jung NH, Delvendahl I, Kuhnke NG, Hauschke D, Stolle S, Mall V. Navigated transcranial magnetic stimulation does not decrease the variability of motor-evoked potentials. Brain Stimul. 2010;3(2):87–94.

Kiers L, Cros D, Chiappa KH, Fang J. Variability of motor potentials evoked by transcranial magnetic stimulation. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1993;89(6):415–23.

Sloan T, Sloan H, Rogers J. Nitrous oxide and isoflurane are synergistic with respect to amplitude and latency effects on sensory evoked potentials. J Clin Monit Comput. 2010;24(2):113–23.

Koitabashi T, Johansen JW, Sebel PS. Remifentanil dose/electroencephalogram bispectral response during combined propofol/regional anesthesia [see comment]. Anesth Analg. 2002;94(6):1530–3.

Kopp Lugli A, Yost CS, Kindler CH. Anaesthetic mechanisms: update on the challenge of unravelling the mystery of anaesthesia. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2009;26(10):807–20.

Son Y. Molecular mechanisms of general anesthesia. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2010;59(1):3–8.

Campagna JA, Miller KW, Forman SA. Mechanisms of actions of inhaled anesthetics. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(21):2110–24.

Bonhomme V, Boveroux P, Hans P, Brichant JF, Vanhaudenhuyse A, Boly M, Laureys S. Influence of anesthesia on cerebral blood flow, cerebral metabolic rate, and brain functional connectivity. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2011;24(5):474–9.

Rudolph U, Antkowiak B. Molecular and neuronal substrates for general anaesthetics. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5(9):709–20.

Jones MV, Harrison NL. Effects of volatile anesthetics on the kinetics of inhibitory postsynaptic currents in cultured rat hippocampal neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1993;70(4):1339–49.

Chau PL. New insights into the molecular mechanisms of general anesthetics. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;161:288–307.

Chortkoff BS, Eger EI 2nd, Crankshaw DP, Gonsowski CT, Dutton RC, Ionescu P. Concentrations of desflurane and propofol that suppress response to command in humans. Anesth Analg. 1995;81(4):737–43.

Dwyer R, Bennett HL, Eger EI 2nd, Heilbron D. Effects of isoflurane and nitrous oxide in subanesthetic concentrations on memory and responsiveness in volunteers. Anesthesiology. 1992;77(5):888–98.

da Costa VV, Saraiva RA, de Almeida AC, Rodrigues MR, Nunes LG, Ferreira JC. The effect of nitrous oxide on the inhibition of somatosensory evoked potentials by sevoflurane in children. Anaesth Intensiv Care. 2001;56:202–7.

Manninen PH, Lam AM, Nicholas JF. The effects of isoflurane and isoflurane-nitrous oxide anesthesia on brainstem auditory evoked potentials in humans. Anesth Analg. 1985;64(1):43–7.

Samra SK, Vanderzant CW, Domer PA, Sackellares JC. Differential effects of isoflurane on human median nerve somatosensory evoked potentials. Anesthesiology. 1987;66(1):29–35.

Hosick EC, Clark DL, Adam N, Rosner BS. Neurophysiological effects of different anesthetics in conscious man. J Appl Physiol. 1971;31(6):892–8.

Griffiths R, Norman RI. Effects of anaesthetics on uptake, synthesis and release of transmitters. Br J Anaesth. 1993;71(1):96–107.

Stabernack C, Sonner JM, Laster M, Zhang Y, Xing Y, Sharma M, Eger EI 2nd. Spinal N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors may contribute to the immobilizing action of isoflurane. Anesth Analg. 2003;96(1):102–7.

Zhang Y, Laster MJ, Hara K, Harris RA, Eger EI 2nd, Stabernack CR, Sonner JM. Glycine receptors mediate part of the immobility produced by inhaled anesthetics. Anesth Analg. 2003;96(1):97–101.

Mashour GA, Forman SA, Campagna JA. Mechanisms of general anesthesia: from molecules to mind. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2005;19(3):349–64.

Haghighi S, Madsen R, Green K. Suppression of motor evoked potentials by inhalation anesthetics. J Neurosurg Anesthes. 1990;2:73–6.

Haghighi SS, Green KD, Oro JJ, Drake RK, Kracke GR. Depressive effect of isoflurane anesthesia on motor evoked potentials. Neurosurgery. 1990;26(6):993–7.

Loughnan BA, Anderson SK, Hetreed MA, Weston PF, Boyd SG, Hall GM. Effects of halothane on motor evoked potential recorded in the extradural space. Br J Anaesth. 1989;63(5):561–4.

Zentner J, Albrecht T, Heuser D. Influence of halothane, enflurane, and isoflurane on motor evoked potentials. Neurosurgery. 1992;31(2):298–305.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sloan, T.B., Toleikis, J.R., Toleikis, S.C. et al. Intraoperative neurophysiological monitoring during spine surgery with total intravenous anesthesia or balanced anesthesia with 3 % desflurane. J Clin Monit Comput 29, 77–85 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10877-014-9571-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10877-014-9571-9